College Like Kindergarten? Students Need Cookies, Coloring Books, Bubbles, Play-Doh, Blankies and Frolicking Puppies, Some Say

Wow. Where are the adults anymore?

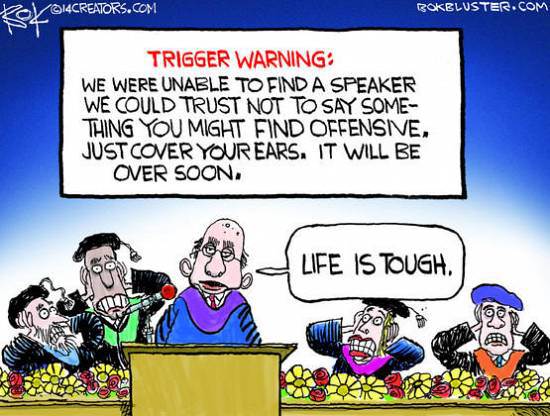

Higher education professionals are dismayed at the growing number of students who expect their universities to protect their tender emotions from over-stimulation.

If you graduated from college in the previous millennium, you may be unaware that many students now believe that college professors and administrators should protect them from, rather than expose them to, ideas they disagree with, especially ideas that disturb them.

Much of the recent debate over the current state of college campuses was spurred by Judith Shulevitz's March 21 op-ed in The New York Times, "In College and Hiding From Scary Ideas."

The Brown University campus, Shulevitz wrote, provided a "safe space" during a debate about campus rape, which was a room "equipped with cookies, coloring books, bubbles, Play-Doh, calming music, pillows, blankets and a video of frolicking puppies ..."

While high school graduates were once considered adults, college students are now treated like kindergartners.

While high school graduates were once considered adults, college students are now treated like kindergartners.

In a February article for Slate, a liberal publication, Eric Posner defends the recent rash of speech code and "trigger warnings" on college campuses that mostly target conservatives and libertarians, but occasionally catch liberals. The reason colleges should protect students from being exposed to alternative ideas, Posner wrote, is that college students are children and "must be protected like children."

At the University of Michigan, students objected to the film "American Sniper" on campus, so the administration initially scrapped it in favor of "Paddington," a PG-rated film adapted from a children's book about an anthropomorphized teddy bear. This prompted one conservative commentator to complain that the campus was turned into "bubble-wrapped ball pits — daycare for crybabies."

At Smith College last year, author Wendy Kaminer spoke on a panel about the freedom of speech on college campuses. It was called, "'Challenging the Ideological Echo Chamber: Free Speech, Civil Discourse and the Liberal Arts." During the discussion, she noted that there is a difference between using a slur and describing a slur. She spoke about the difference, while teaching about The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, of a teacher saying "n-word," or saying, as appears in the original text, "******," versus using an epithet as a slur.

After saying the actual "n-word" (instead of saying "n-word"), Kaminer remarked, "nothing horrible happened."

In noting the dangers of speech codes, she recalled a professor who was found guilty of racial harassment because he said "wetback" in explaining to the class that the word "wetback" is used as a pejorative for undocumented Mexican immigrants.

"Well that's just ridiculous, Wendy, but I don't think that's comparable to this," another panelist, Jaime Estrada, replied.

The comparison would turn out to be more apt than Estrada realized at the time.

A group of Smith students described Kaminer as committing "an explicit act of racial violence" and denounced Smith President Kathleen McCartney, who was also on the panel, for not condemning Kaminer right away.

Ironically, Kaminer's critique of censorship on college campuses was censored when the student newspaper published a transcript of the event.

The "soft authoritarianism that now governs many American campuses," Kaminer wrote for The Washington Post, does not advance equality; rather, it teaches "future generations of leaders the 'virtues' of autocracy."

In another incident mentioned by Shulevitz, Zineb El Rhazoui, a journalist from Charlie Hebdo, the French satirical magazine that was attacked by Muslim extremists, spoke at the University of Chicago. In response, an opinion writer in the student newspaper complained that El Rhazoui did not ensure "that others felt safe enough to express dissenting opinions" and spoke from a "relative position of power."

The students who sponsored the talk replied that unlike the student who felt unsafe, El Rhazoui is actually "living in very real fear of death. She was invited to speak precisely because her right to do so is, quite literally, under threat."

Shulevitz summarized the situation well: "You'd be hard-pressed to avoid the conclusion that the student and her defender had burrowed so deep inside their cocoons, were so overcome by their own fragility, that they couldn't see that it was Ms. El Rhazoui who was in need of a safer space."

In an article for Reason, Lenore Skenary ties the trend to off-campus cultural trends for an article called, "College Students: Stop Acting Like You're Made of Sugar Candy."

As a libertarian publication, Reason has been at the forefront in covering laws and bureaucrats that assume citizens are incapable of making good choices so the government must make those choices for them.

Reason helped bring attention, for example, to Maryland parents who were told they could lose custody of their children after they let them play outside unsupervised.

"What happens," Skenary wrote, "when a generation grows up being told that nothing is safe enough, not even a walk home from the park? ... Here's what happens: At least a portion of them become convinced that they are extremely fragile. They need — they demand — the kind of life-buffers they've had since childhood."

Some professors, even liberal professors, are now beginning to worry that the current climate could threaten their livelihood.

A blog post from an anonymous liberal professor has been offered in many of these discussions as an example of the fear felt by professors these days.

He mentioned the case of Laura Kipnis, a professor in the department of radio, television, and film at Northwestern University, who wrote an article for The Chronicle of Higher Education decrying the "paranoia" on campuses over new sexual harassment policies.

Kipnis teaches film classes. Typically this means watching a film, engaging in class discussions about the film, and writing critical essays about the film. Two students approached her one day and asked that they be allowed to not participate in the viewing and class discussion for one film because it "triggered" something (they did not specify want). Kipnis wondered if she would be preparing them for life after college to grant their request.

"I had an image of her in a meeting with a bunch of execs, telling them that she couldn't watch one of the company's films because it was a trigger for her. She agreed this could be a problem, and sat in on the discussion with no discernable ill effects," Kipnis wrote.

In reaction to Kipnis' article, students (triggered students?) accused her of violent, "inflammatory" and "terrifying" ideas, and asked administrators to punish her.

Regarding the Kipnis case, the anonymous professor wrote: "This is a matter of real, palpable fear. Saying anything that goes against liberal orthodoxy is now grounds for a firin'. Even if you make a reasonable and respectful case, if you so much as cause your liberal students a second of complication or doubt you face the risk of demonstrations, public call-outs, and severe professional consequences."

The problem, the liberal professor continued, is not with his conservative students.

"Personally, liberal students scare the [expletive] out of me," the professor wrote.

If a conservative student complains to administrators about his liberal bias, the professor explained, he still gets to keep his job. But one wrong move that upsets a liberal student, even if it is unintentional or just makes them uncomfortable, and, the professor fears, his career could be over.

"Is this paranoid?" he continued. "Yes, of course. But paranoia isn't uncalled for within the current academic job climate. Jobs are really, really, really, really hard to get. And since no reasonable person wants to put their livelihood in danger, we reasonably do not take any risks vis-a-vis momentarily upsetting liberal students. And so we leave upsetting truths unspoken, uncomfortable texts unread."

n 2013, about 25 UCLA graduate students in the Department of Education protested one of their professors for correcting their grammar in a course desinged to prepare them to write a dissertation. By pointing out that "indigenous" should not be capitalized, and by preferring the Chicago Manual of Style over the American Psychological Association style guide, the professor was guilty of "microaggressions" against students of color and "contributed to a hostile class climate," the protestors claimed.

This story, and other examples of microaggressions posted to www.microagressions.com (such as asking someone if they have ever been to Europe), prompted one combat veteran to write: "Generations of Americans experienced actual trauma. Our greatest generation survived the Depression, then fought the worst war in humanity's history, then built the United States into the most successful nation that has ever existed. They didn't accomplish any of that by being crystal eggshells that would shatter at the slightest provocation, they didn't demand society change to protect their tender feelings. They simply dealt with the hardships of their past and moved on."

That article was intially removed from Facebook, because it was "detected to be unsafe."

Wow. Where are the adults anymore?